“Daddy died three years ago because of the disease called AIDS.” Taohua (not her real name) is a skinny 11-year-old girl with a pony tail, shy but well-spoken. “First he had a headache. Then he got very sick and went to see a doctor, but he just got sicker. Mom wanted to buy some medicine, but our family was too poor. So Daddy didn't want Mom to spend the money.” As she remembered, her eyes started to fill with tears: “He was sick at home for more than a year. After the funeral, one of my aunts bought me some clothes. Some relatives and neighbors gave us money and food, so we got enough to eat.”

Taohua's family grows wheat and peanuts on a plot of land in a sleepy village in the middle of the vast flatland of Henan Province. The main form of transportation for the villagers is still the bicycle; if a car comes down the dirt road, people come out to see who the visitors are. The houses are all of brownish-red brick, without a store or a factory in sight. Apart from residences, the only two buildings are the village office and the medical clinic. The massive wave of urbanization washing over coastal China hasn't reached here yet.

But HIV/AIDS has. In the early 1990s, several blood collection centres were set up near the village. Many villagers sold blood to supplement their income, happy to earn RMB 40 for each visit. They were told they would recover quickly from the loss of blood after plasma mixed with that from other blood donors was pumped back into them. This is how HIV spread in this conservative rural area, where extramarital sex and drug use are rare. According to official statistics, more than 10,000 HIV/AIDS cases were reported in Henan province in 2003.

“Mom works hard every day,” says Taohua. “She's very tired but doesn't want me or my two sisters to help her in the fields. She wants us to study. I help her with cooking. I also wash our clothes.” The skin of Taohua's tiny hands is rough. At the village elementary school, she has 37 classmates, all of whom know her situation. But she has never talked about AIDS or her father's death with her friends, her older sisters, or even with her mother.

“What I'm most worried about is my mother. She hasn't been feeling well lately,” Taohua says in a small voice. Then she adds: “Daddy sold blood twice but Mom has never done it.” According to a local official, Taohua doesn't know her mother is HIV-positive, most likely as a result of secondary transmission from her late husband.

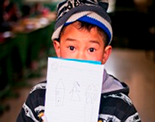

“I hear AIDS can't be cured,” Taohua says. “But when I grow up, I want to become a doctor and cure everybody.”

Like Taohua, about 130 children in her village have already lost one or both parents to AIDS. In the whole of Henan province, more than 2,000 children have been identified as so-called “AIDS orphans,” most of them between ages six and 15. Some are HIV-positive themselves. Some mothers have remarried and moved away after the death of their first husband. If the surviving parent is too sick to take care of the children, the youngsters live with their grandparents or in a welfare centre.

Mrs. Li (not her real name), who lives in another county in Henan, had to send her 12-year-old daughter to the welfare center after her husband died of AIDS in 2002. “I got so sick I couldn't take care of my two children any more,” she said. “I asked my mother and relatives in another village if my younger daughter could live with them, but they refused to take her because they're scared of AIDS—even though my daughter isn't infected. People in other villages are afraid of us. They don't want to talk to us. They won't sit next to us. They don't want to buy vegetables from us.”

Mrs. Li went to look at the welfare centre where about 20 children of AIDS sufferers reside. “I've never talked about HIV/AIDS with my children,” she continues. “They never ask me about it either, but I know they know. Many people died in our village. I told my daughter: ‘I'm sick. Going to the welfare centre is good for me and good for you.' She didn't say anything, but she understands.”

Local governments in Henan waive school fees for children affected by HIV/AIDS and provide HIV/AIDS training to school teachers. Other measures include free testing, medical care, and medicines; ensuring the use of disposable needles and syringes; prevention of mother-to-child transmission; road construction in villages affected by HIV/AIDS; provision of water to every household; free flour and low-cost supplies for families in especially difficult economic conditions; and exemption from a variety of local taxes.

This support definitely helps. In fact, some healthy villagers have been known to pretend they are HIV positive or that a family member is an HIV/AIDS patient to gain access to these benefits.

UNICEF China, with funding from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), has been supporting the government's effort in two counties in Henan since 2001. During a monitoring trip in March 2004, Dr. Koenraad Vanormelingen, chief of the UNICEF China health section, was impressed by the progress made since his previous visit six months earlier. “With a relatively small financial input and technical support from UNICEF, the local authorities have already taken a number of significant actions,” he said. “I can see the difference already.”

The UNICEF China office and other UN agencies and development partners formed a UN theme group on HIV/AIDS. The group urges Chinese authorities to make HIV/AIDS a consistent priority, and the government has responded by strengthening its commitment to dealing with HIV/AIDS.

Authorities in Henan have put together a 10-year plan of action to deal with the disease. HIV/AIDS leadership committees are being established at each administrative level. Each government agency now has clearly designated roles and responsibilities, and a number of technical training sessions have been conducted. Local officials have had posters and leaflets printed explaining how the virus can and cannot be transmitted. They have also organized public events attended by more 10,000 people each. Local TV and radio stations are also airing many programmes on HIV/AIDS.

Still, there is a long way to go.

Psychological counseling and care for children affected by HIV/AIDS clearly needs to be strengthened. Most parents living with HIV/AIDS never talk to their children about the disease. Children who grow up in this atmosphere of portentous non-discussion are often sad and anxious, and avoid the subject themselves. Like their parents, they suffer in silence. One article written by an AIDS orphan states, “My father died in order to pay my school fees.” Such self-blame can easily have a life-long negative impact on children. UNICEF China is committed to providing the technical assistance needed to strengthen psychological care for children, a substantially new field in China.

UNICEF China is also taking up the challenge of fighting the social stigma attached to HIV/AIDS and the discrimination against HIV/AIDS victims and their families. This work will focus on young people in cooperation with a number of youth organizations and the sports and entertainment sectors. “Youth participation is the key to the success of this campaign,” says Charles Rycroft, chief of communication for of UNICEF China. “Children themselves will select celebrities and will take initiatives to be one of the cool agents of change.”