After losing her mother to the Ebola virus, a girl in Sierra Leone must raise her younger brother and sister on her own – and hold on to her own hope of returning to school.

©UNICEF/Sierra Leone/2014/Bindra ©UNICEF/Sierra Leone/2014/Bindra

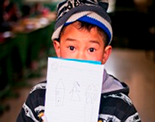

Amadou and his sister, Awa, at the family's home in Kenema, Sierra Leone |

KENEMA, Sierra Leone, 16 October 2014 – Four-year-old Amadou wakes up his sister, Mary, at 4:30 a.m. He has a headache and can't sleep. He asks her where their mother is. It is the same question he has asked almost daily since he was discharged from the Ebola Treatment Unit in Kenema, almost two months ago.

Mary, 15, ignores her initial annoyance at being woken up and becomes gentle. She brings him into her bed and drapes her thinning bedcloth over him, smoothing it over his fragile body.

“I don't know what to tell him,” Mary says. “How can I explain death to a 4-year-old when I barely just understood it myself? This wasn't supposed to be my responsibility.”

Forced to grow up quickly

Nearly 600 children have lost one or both parents to Ebola since the start of the outbreak in Sierra Leone. Across West Africa, children face stigma and rejection from their communities and their relatives, especially if the children are survivors themselves. Like Mary, they have been forced to grow up quickly.

©UNICEF/Sierra Leone/2014/Bindra ©UNICEF/Sierra Leone/2014/Bindra

Mary, 15, at home with her brother and sister |

“My mother was the first to fall sick, after helping a sick woman in the neighborhood,” she says. “She thought she had malaria, but her condition worsened rapidly. They called for an ambulance, and she was rushed away to the General Public Hospital in Kenema. It was the last time that I saw her.”

Her mother died few days later, but it was a month before the hospital announced her death.

“I'm sad. When my mum was alive, she used to encourage me,” she says. “We talked a lot. We laughed before going to bed. We had a lot of fun together. Since she died, nobody can talk to me the way that she did. I'm really missing her, her love, everything. When we were sitting quietly, she told me the story of her and my dad, their separation, his journey abroad – all these things that I've been missing.”

No time to mourn

While many children have extended families that can take the children in, Mary has lost much of her extended family to the virus and is now relying on the help of neighbours to get by.

“I don't have time to mourn the death of my mother. I can only try to make Amadou and Awa [her younger sister] happy,” Mary says. “I cook for them, and I clean the house. The neighbors were afraid of us at first, but after the social workers talked to them, they began to give us some rice from time to time. We have no resources at all, and we're facing a lot of challenges.”

Some of her friends have run away from her, she says. “They don't want to talk to me anymore, they're afraid of me. My best friend's sister also contracted the disease – she knows about Ebola, all these things. We often talk about it, how my mum got sick, our reactions, our feelings.”

Remaining hopeful

“You know, the worst is not being able to go back to school. My mum promised me that I will be educated,” Mary says. “She wanted me to be a nurse. Classes are closed now, but I fear not being able to go back when they will reopen.”

UNICEF is appealing for US$61 million to meet the dire needs of children and families affected by the outbreak, but so far less than 40 per cent has been received.

Despite facing hardships she never imagined, Mary remains hopeful. “First, I will take care of my brother and sister, then I will take care of our people. There must be a reason why we survived, so we have no other choice but to keep surviving.”

By Anne Boher