By Antony Spalton

By the end of the 1990s, climate-change related disasters affected about 66 million children per year. In the coming decades, this number is expected to triple, to 200 million children annually. Sadly we can expect to see more child deaths caused by disasters. More children will face great physical and psychological peril. More will not be able to go to school and will be at risk of trafficking, abuse, exploitation and forced labour as a consequence of disasters.

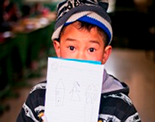

©UNICEF/NYHQ2011-0427/Dean

Neena (5) surveys the wreckage of her home, which was destroyed by the 2011 tsunami in Japan. |

The new Global Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) to be agreed at the World Conference in Sendai, Japan, is about taking more ambitious steps to nip disasters in the bud.

While we may not be able to prevent floods, drought and earthquakes, we have learnt that steps can be taken to reduce the risk. Sendai is about agreeing on these measures and committing to making them happen. Youth and children will be there to help this happen. We must listen to what they have to say, and involve them in dialogues, decisions and finding solutions.

Somebody once said ‘earthquakes don't kill children, buildings kill children'. There is some truth here. Hazards such as floods and earthquakes, don't have to be disasters. Buildings, such as schools, should protect children and not kill them. Simple measures such as enforcing building codes, teaching children to ‘duck, cover and hold' in the event of a quake or school drills, do save lives.

©UNICEF/NYHQ2011-1591/Bell

Fourth-graders seek shelter under a table during an earthquake preparedness exercise at a school in Kazakhstan. |

But the Conference in Sendai isn't just about being prepared. It's about getting at those issues that make people vulnerable in the first place. It's about the inequity that keeps children out of school, denies them healthcare, and means that they live where others will not – on floodplains, low-lying coastal areas or in unplanned urban slums. It is the poorest of the poor who literally live ‘in harm's way' and disasters pretty much keep them there.

Development, if done well, and if it looks at the hazards to understand who is vulnerable and how, is good DRR. It can lift people out of poverty, give them a voice and move them from harm's way. But gains can be fragile and we must protect them. In Ethiopia, for example, investment in community health and nutrition programmes, basic services that many take for granted, saved thousands of lives in the 2012 drought. And this is not an isolated case.

©UNICEF/UKLA2014 – 1564/Matas

Community swimming instructor, Sufiya Akter (21) leads a swimming lesson which is a part of the UNICEF-supported Swim Safe programme in Bangladesh. |

Some progress has been made, but it's not enough. With this likely tripling of the number of children affected by disasters in the coming decades, something needs to change. The new DRR framework needs to deliver, not only for the children and young people of today, but for the millions who will inherit a world that will see increased disasters and more severe climate. Disaster risk, like climate change, is an inter-generational concern.

And we have a pretty good idea of what works, but it's a question of scale. Breaking the cycle of crises that affect too many children and families requires investing in the simple but effective measures to reduce the impact of natural hazards, tackle the underlying causes of vulnerability, and enhance preparedness.

Learning from successful experiences in places such as in Mozambique, Armenia and Nepal, can we not make every school a safe school? And the experience of Niger, where investment in health systems has actually reached the poor and enabled them to deal with droughts? Can this not become good development practice everywhere in the world?

Antony Spalton is the Risk Reduction and Resilience Specialist with UNICEF's Programme Division.