By Li Tianxing, consultant at UNICEF China's Education Section

It was raining heavily in Shanghai, the impact of Typhoon Haima. But no downpour could wash out or dampen the enthusiasm for the first-ever Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Expo, jointly launched by the China Friendship Foundation for Peace and Development and United Technologies Corporation in October 2016. The three-day expo connected education institutions, non-government organizations and businesses and concluded with the exciting final competition for Future Makers, organized by Shanghai Science Association for Young Talents.

I wandered the events on education advancement, future careers, diversity, and inclusion and sustainable development, finding inspiring ideas and amazing young talent. Like Chen Fengyun.

©UNICEF/China/2016/Li Tianxing ©UNICEF/China/2016/Li Tianxing

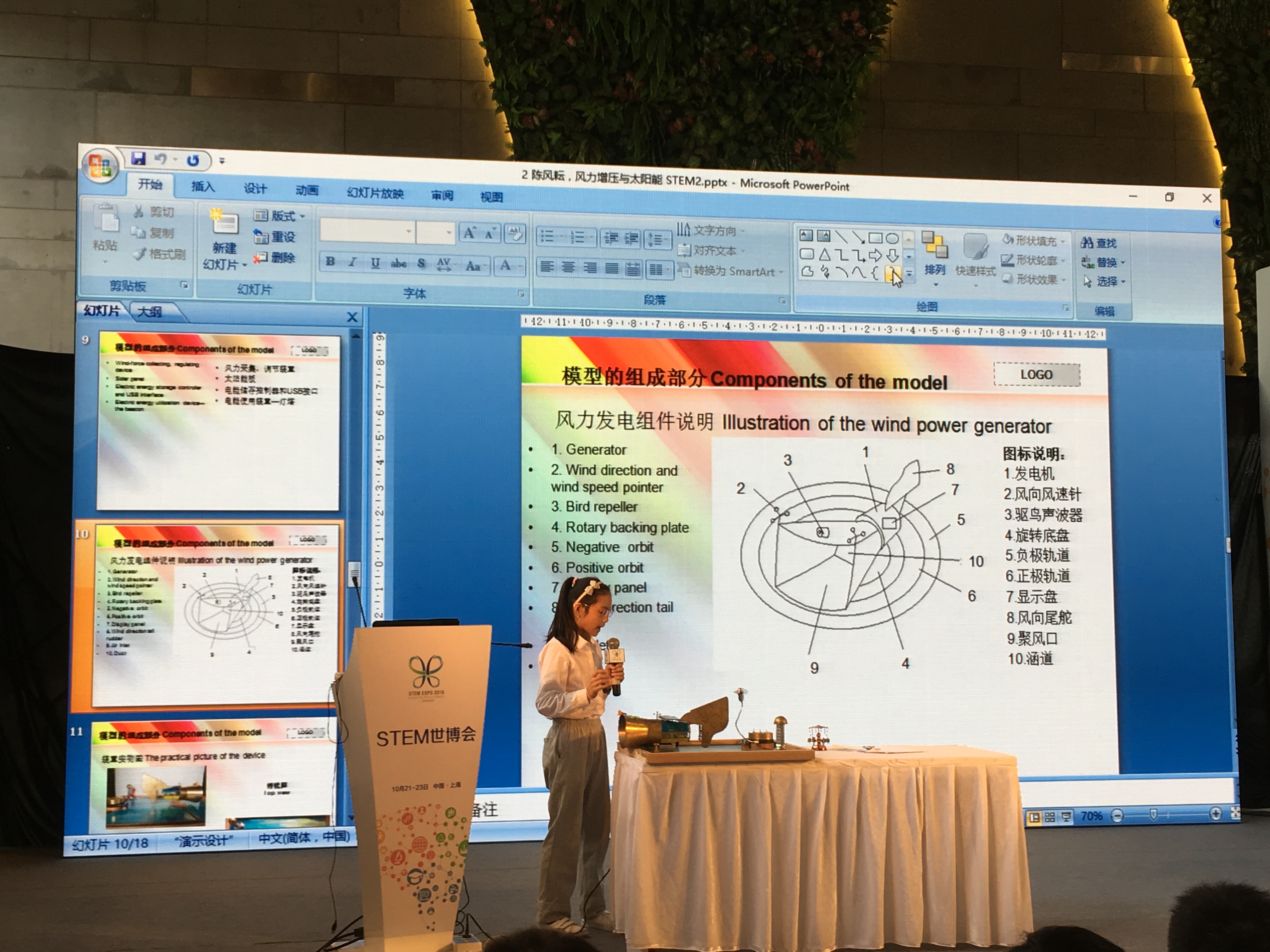

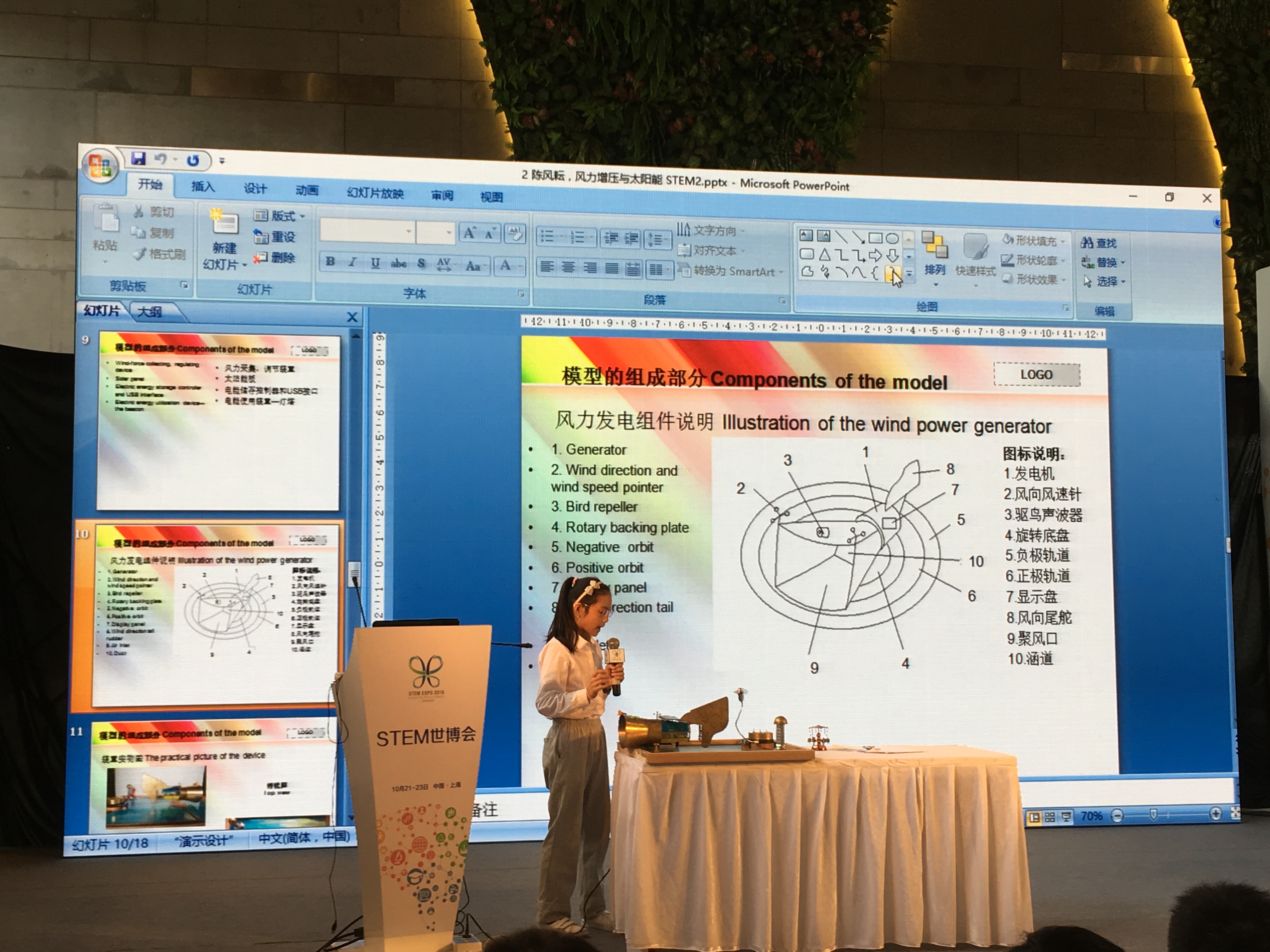

Chen Fengyun introduces her invention at the STEM Expo in Shanghai. |

Twelve-year-old Chen Fengyun is from Shanghai and just started the sixth grade. When I met her, she was talking about her invention – a power-generating device that uses both wind and solar energy – that she started developing in the first grade. She had already introduced her project to various other domestic and international science competitions – in Chinese and English. Here at the expo, she was one of the youngest participants in the Future Maker competition (with students up to grade 11). She tied for Best Presentation.

Both STEM and maker education are increasingly popular in the education field globally and in China.

STEM education looks beyond knowledge and skills in those fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) to create an exploratory environment for learners, leading students to solve real-world problems and create opportunities for themselves in the process. This invigorating process stimulates creativity, critical thinking and problem-solving abilities of students.

Maker education equates learners with “makers” (creators) and the learning process with “making something new”. Maker education helps learners turn their ideas into actual products. Despite its emphasis on using tools and completing a final product, maker education overlaps with STEM education in terms of the knowledge and core competencies it teaches students.

Both concepts tap into the Government of China's support for mass entrepreneurship and innovation by motivating creative thinking at the earliest age. Wandering the expo, I felt the exciting twinges of a country about to break new ground in cutting-edge ways of thinking.

Seeing the opportunities available for many young students also gave me pause, when I thought about the millions of Chinese children in the rural regions of western China where education resources (books and computers, for starters) and teacher quality are poor and where it is extremely difficult for schools to access expensive equipment, like 3D printers and virtual reality simulators. Teachers in western China lag behind their eastern counterparts in terms of their own education and training. Understanding STEM education is likely a huge challenge for many of them, let alone their capacity to teach the difficult concepts.

But this is where UNICEF's latest work gives me something to smile about.

From 2011 to 2015, UNICEF offered teacher training to enhance teachers' ability to teach math, Chinese and science subjects for grades 3–5. The Skills, Motivation and Imagination for Learning Excellence' (SMILE) Programme developed around 40 games to help improve students' learning as well as their practical and innovation skills in those three subjects.

©UNICEF/China/2016/Li Tianxing

SMILE games that the audience found stimulating.

|

The games targeted difficult areas of teaching, as identified by surveys, and offered ways for students to reinforce their understanding of difficult concepts while having fun.

And now, the three years of testing the programme in five counties of five western regions (Chongqing, Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou and Xinjiang) have delivered amazing results. From an improved classroom model of teaching and to the extensive popularization of “learning is fun” and “creativity through games” notions among children and parents, change is taking root.

©UNICEF/China/ Pam Vachatimanont

A few students in Zhong County, Chongqing, play Panda's Feast to familiarize with the concept of remainders in division through game.

|

Those results and the SMILE Programme's experiences were introduced at the STEM Expo by UNICEF China's Education Specialist Dr. Guo Xiaoping. She also showed the audience some of the games that were developed for the programme. Her presentation attracted much interest from the audience of educators, and many people approached her afterward with questions on the resources developed, hoping to use these resources and models to better engage students in STEM education.

©UNICEF/China/2016/Li Tianxing

Dr. Guo Xiaoping, UNICEF China Education Specialist, introduces experience from UNICEF's SMILE programme at the STEM Expo in Shanghai. |

It is my hope that programmes like SMILE will help more students build a solid foundation of STEM knowledge so that they will one day use it to make opportunities for themselves, as Chen has been able to do.

©UNICEF/China/2016/Guo Xiaoping ©UNICEF/China/2016/Guo Xiaoping

The writer attends STEM Expo in Shanghai. |

Li Tianxing is a consultant with UNICEF China's Education Section.